Understanding the dairy cow is a matter of heart and mind. We need to consider her scientifically as a complex and elegant biological instrument to provide us with milk, the nearest thing in nature to a complete food. The cow was one of the first animals to be domesticated for human use and has come a very long way since then. The traditional role of the family cow was to provide milk, work, fertiliser, fuel and clothing, while sustained by fibrous feeds that the family could not digest for themselves, usually from land that the family did not own.

The modern dairy cow, typified by the Holstein breed, is a very different creature: bred, fed and managed to produce as much milk as possible within intensive, highly mechanised dairy units. Not only does she have a conspicuously larger udder, she is bigger framed, much more rhomboid in shape and carries much less muscle. This phenotype is the consequence of a breeding policy designed to ensure the production of as much milk as possible from individual cows spending most of their adult life in barns on a diet of rich feed.

To understand nutrition and feeding we have to understand digestive system of cows. Digestion is the process whereby food is broken down into substances that can be absorbed across the cell lining of the intestine. The nutrients made available by digestion and absorption are then available for metabolism by the tissues of the body to meet the needs of maintenance, work, growth, reproduction and lactation. One of the most fundamental and characteristic thing about the biology of cows is that “they are ruminants”, now a question arises! What is a ruminant?

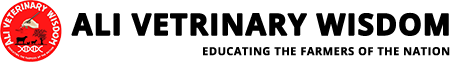

Animals which have rumen are called ruminants. They have four compartments to their digestive system – the rumen, reticulum, omasum and abomasum. These are often referenced as the four ‘stomach chambers’ of a ruminant animal.

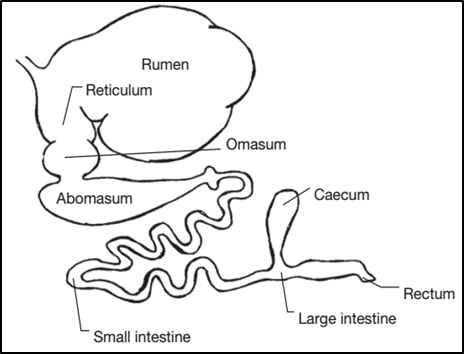

At birth, calf do not have well developed rumen and its associated structures (reticulum and omasum). Calf only have abomasum, which is true stomach like we have. When calf suckles milk from mother cow, it directly goes into abomasum bypassing rumen. It occur through esophageal groove. If milk enter inside early rumen of calf, it start rotting and cause indigestion. It must be digested in abomasum.

Slowly and steadily rumen start developing as calf start nibbling fiber in its diet. Microbial population, both number as well as diversity begin to grow which helps in development of rumen and reticulum. It helps in adaptation of calf to have fiber rich diet. By the end of 3 months calf would have fully functional rumen and it can have all those things which adult cow can consume.

Rumen development is most important event in cow’s life. Early rumen development helps in early switching of calf to high fiber diet which reduces feed expanses. In adult cows, rumen and reticulum enlarged and 60 – 70% of total digestion occurs inside rumen.

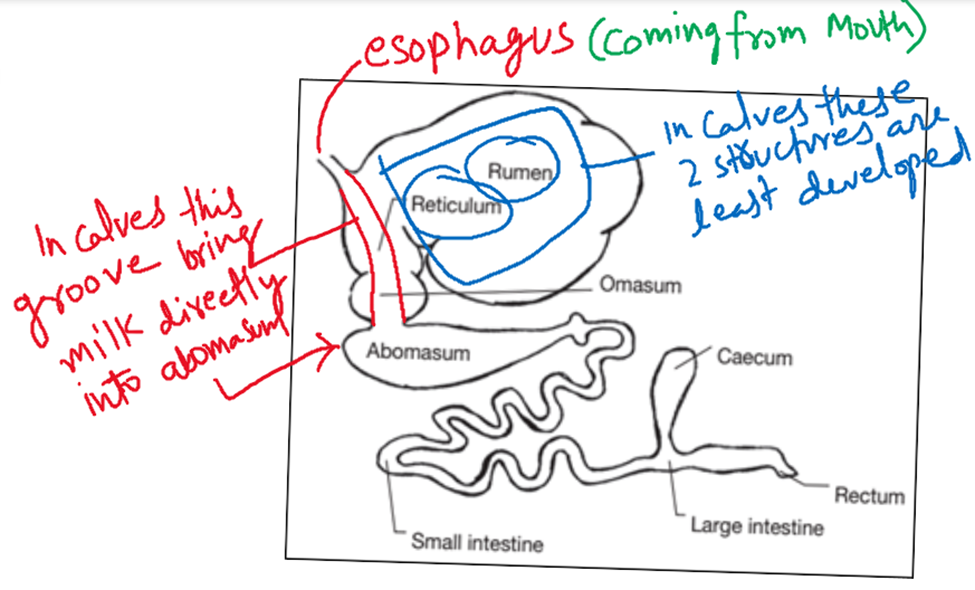

In adult cow once food has been ingested, it is briefly chewed and mixed with saliva, swallowed and then moved down the oesophagus into the rumen. The rumen is adapted for the digestion of fiber. It is the largest compartment of the adult ruminant stomach. The rumen is sometimes described as a ‘fermentation vat’. Its internal surface is covered with tiny projections, papillae, which increase the surface area of the rumen and allow better absorption of digested nutrients.

The reticulum is separated from the rumen by a ridge of tissue. Its lining has a raised honeycomb-like pattern, also covered with small papillae. The rumen and reticulum together have a capacity of 50 to 120 L of food and fluid. The temperature inside the rumen remains stable at around 390C (range 38–420C) which is suitable for the growth of a range of microbes. The microbes break down feed through the process of fermentation. Under normal conditions, the pH of the contents of the rumen and reticulum is maintained in the range.

The ‘third’ stomach, or omasum, is made up of more than 100 leaves (hence psaltery) of epithelial tissue, so that while the mass of the empty omasum is relatively large (16%), it contains only about 4% of total digesta. This is packed between the leaves of epithelium and tends to be very dry, suggesting that the main role of the omasum is the absorption of water and substances in solution.

The fourth stomach abomasum is the true, gastric stomach of the animal, similar in function to the stomach of monogastrics (e.g. chickens, dog and humans). Protein and some fats are digested in the abomasum with the aid of hydrochloric acid and enzymes.