Cow Not Eating, Cow Not Standing Up, Cow Not Giving Milk – The Real Reason Farmers Miss Until It Is Too Late

A Post-Calving Cow That Stopped Eating, Milk Crashed, and Slowly Went Down – A Case Study from Field Practice

This case came to us through an online consultation request. The farmer’s first message was short but worrying: “Doctor, cow not eating, milk almost finished, uth bhi kam rahi hai.”

These exact words are what thousands of farmers type every day on Google – cow not eating, cow not giving milk, cow not standing up – but behind these words there is always a long story that starts much earlier.

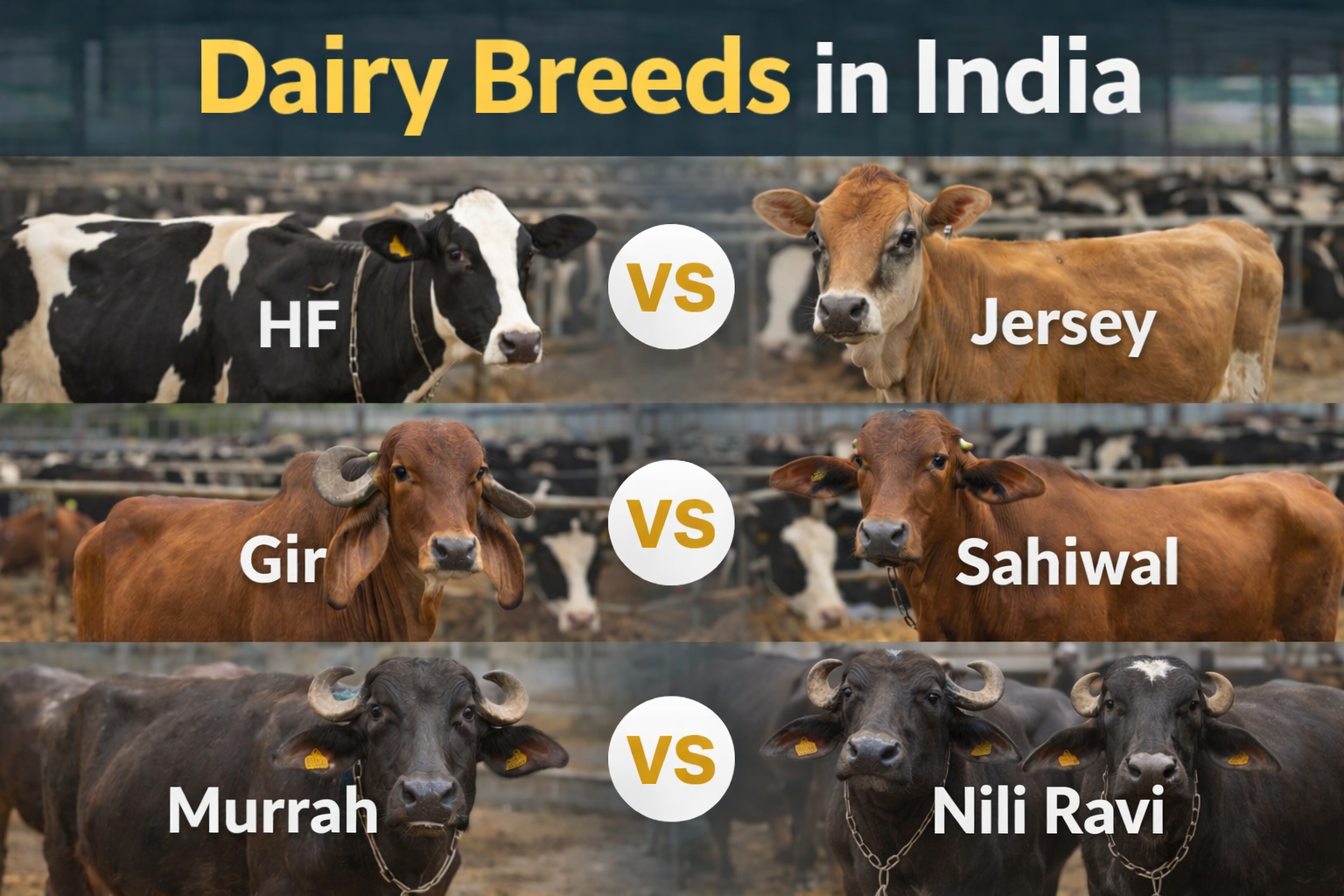

The cow was a second-lactation animal, around 500 kg body weight, with good genetic potential. In her first lactation, she had crossed 30 litres at peak. Calving had occurred around three weeks earlier. Initially everything looked normal, but the afterbirth did not come out completely and a portion remained inside the uterus for several days. Five days later it expelled on its own. That moment, which many farmers consider “problem solved”, was actually the beginning of a much deeper issue.

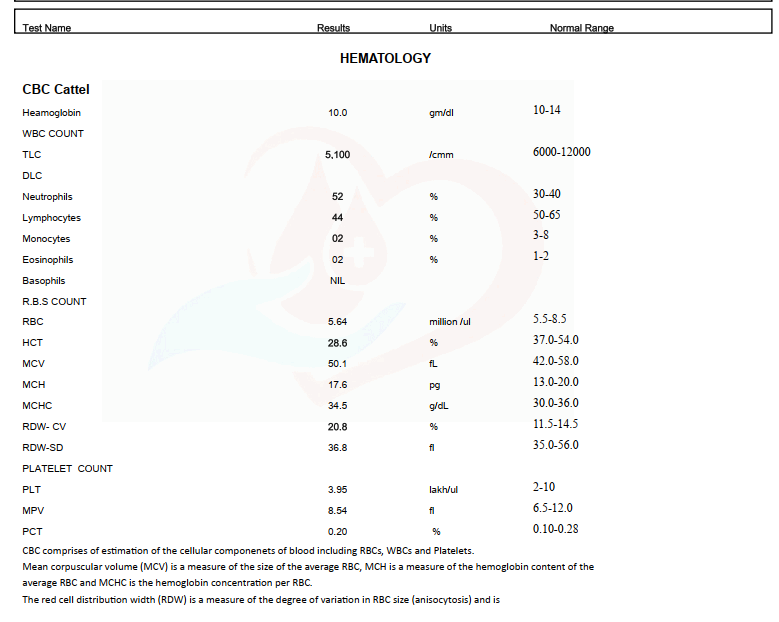

What the Blood Report Revealed in This Case

As part of the online consultation, a complete blood count was advised because the clinical picture did not match a simple uterine infection. The cow was dull, off-feed, milk had crashed, and yet persistent high fever was absent. This mismatch itself was a strong indication that the problem was more metabolic and toxic rather than purely infectious.

The blood report showed haemoglobin at the lower end of normal, with packed cell volume also reduced. More importantly, the total leukocyte count was below the normal reference range. This finding is often misunderstood in the field. Many practitioners expect leukocytosis in infection, but in postpartum toxic cases, leukopenia is actually more significant. It indicates immune exhaustion and endotoxin absorption rather than an active, febrile infection.

Differential leukocyte count showed a relative increase in neutrophils with a drop in lymphocytes. This pattern is typical of stress-related immune suppression seen in cows suffering from toxic metritis and severe negative energy balance. In such conditions, the immune system is overwhelmed, not activated.

Red cell indices suggested mild anemia and poor tissue oxygenation, which further explains the weakness, dullness, and reluctance to stand despite absence of fever. Platelet count and indices were within acceptable limits, indicating that clotting was not a primary concern.

Blood protozoan screening for theileriosis and anaplasmosis was negative, which helped rule out relapse of tick-borne disease that the farmer initially suspected based on previous lactation history. This was an important turning point in the case, as it prevented unnecessary antiprotozoal treatment and allowed focus to shift toward metabolic and toxic causes.

Overall, the blood report confirmed that this was not a simple infection case. It supported the diagnosis of postpartum toxic–metabolic syndrome with immune suppression, reinforcing the need for rumen revival, metabolic correction, antioxidant support, and rational antibiotic use rather than aggressive, random drug combinations.

The First Missed Signals After Calving

During the first few days after calving, the cow was eating less but still drinking water. Colostrum yield on day one was high, but milk started reducing steadily. By day five, milk had already dropped to nearly half. The cow did not show high fever, so the seriousness of the condition was underestimated.

This is a very common mistake. Many postpartum cows do not show persistent fever even when they are developing toxic uterine infection and metabolic stress. In such cases, appetite suppression happens due to endotoxins and metabolic imbalance, not due to temperature alone.

Within a few days, the farmer noticed the cow not eating properly. First she left some green fodder. Then she stopped touching dry fodder. Finally, even concentrate intake reduced. This is the stage where most farmers start searching cow not eating food or cow not eating grass.

When “Cow Not Eating” Is Actually a Rumen Collapse

By the time the case reached us, the cow was barely eating anything. Milk had crashed to 3–4 litres. Dung had changed colour, becoming darker and tighter. Urine was deep yellow. There was foul-smelling uterine discharge mixed with blood and pus. Still, there was no high fever.

This combination is classic for postpartum toxic metritis with metabolic collapse. But the most important organ affected here was not the uterus alone – it was the rumen.

Whenever a cow stops eating after calving, especially after retained placenta, the rumen is the first system to suffer. Reduced feed intake leads to reduced rumen motility. Reduced rumen motility kills beneficial microbes, often these dead microbes enters blood stream due to weaken rumen lining. Once rumen fermentation slows down, appetite signals to the brain shut off. That is why simply giving antibiotics or fluids does not make such cows eat again.

This is where feed premix for rumen functioning becomes critical. In our consultation, one of the first corrections advised was restoring rumen ecology. Products like Rumenia are designed exactly for such situations, where rumen microbes are suppressed due to stress, toxins, and negative energy balance. But they work in tandem with proper treatment in which inflammation is reduced.

Why the Cow Stopped Eating Grass First

An important detail in this case was that the cow completely stopped eating grass and straw before she stopped concentrate. This is a classic sign that many people ignore.

Grass and roughage digestion require strong fibre-degrading bacteria. These bacteria are extremely sensitive to rumen acidity and toxin load. Once they are affected, grass causes discomfort, bloating sensation, and reduced cud chewing. The cow instinctively avoids it.

That is why, in such cases, yeast-based support with fibre enzymes becomes essential. Pyrosach, which combines saccharomyces cerevisiae with endo-1.4-beta xylanase, helps restart fibre digestion, stabilise rumen pH, and slowly bring the cow back to fodder intake. In many recovered cases, the first positive sign is not increased milk, but the cow starting to chew cud again and picking at green fodder.

Milk Drop Was a Symptom, Not the Disease

The farmer was understandably worried about milk loss. “Cow not giving milk” was his biggest concern. But milk reduction in this case was not the primary problem. It was the body’s survival response.

When a cow goes into severe negative energy balance after calving, the body diverts nutrients away from milk to protect vital organs. Pushing milk at this stage, either through excess concentrate or hormonal shortcuts, only worsens metabolic stress.

Instead, the focus of consultation was shifted towards energy metabolism correction. Excessive fat mobilisation was suspected, which suppresses appetite further. This is where supplements containing niacin and biotin, like Bionice, play a role by reducing fat breakdown, improving glucose availability, and supporting rumen microbes indirectly.

The Hidden Role of Minerals and Oxidative Stress

Another important aspect of this case was immune suppression and slow recovery despite multiple treatments. Blood work showed leukopenia, which pointed towards endotoxemia rather than active feverish infection.

In such situations, trace mineral imbalance and oxidative stress play a huge role. Trace minerals are required for enzyme systems that control digestion, immunity, and muscle function. Long-term deficiencies do not show sudden signs but weaken the animal’s ability to recover.

A balanced trace mineral supplement like Pyromin supports these enzyme systems and improves overall metabolic resilience. Along with this, oxidative stress after calving and uterine infection suppresses appetite and healing. That is why vitamin E and selenium supplementation, such as Sel-E Boost, was advised as part of the recovery plan to neutralise free radicals and support immune function.

Why the Cow Became Weak and Inactive Without Fever

One confusing aspect for the farmer was the absence of fever. He kept saying, “Doctor, bukhar to nahi hai, phir bhi cow kuch kha nahi rahi.”

This is a very important learning point. In toxic postpartum cases, cows often become afebrile or show only mild transient fever. Endotoxins affect appetite centres in the brain, liver metabolism, and rumen motility directly. As a result, the cow becomes dull, weak, and inactive without classic signs of infection.

By the time such cows start lying down more and farmers search cow not standing up or cow not getting up, the problem has already progressed from digestive to systemic.

How Ali Veterinary Wisdom Approaches Such Cases Differently

What made a difference in this case was not one medicine, but the approach. Through Ali Veterinary Wisdom’s online consultancy, the case was analysed as a whole – history, calving events, feed intake pattern, dung changes, urine colour, milk trend, and previous lactation problems.

Instead of treating it as “just uterine infection” or “just not eating”, the problem was identified as a postpartum toxic–metabolic syndrome with rumen collapse at its core.

The guidance focused on stopping further toxin absorption, supporting the liver and rumen, correcting energy imbalance, and strengthening immunity. Antibiotics were rationalised instead of being randomly changed. Rumen support, metabolic correction, mineral balance, and antioxidant therapy were integrated into a single recovery plan.

Recovery Is Slow, But It Comes From the Right Direction

In such cases, appetite does not return overnight. The first signs of improvement are subtle – the cow starts sniffing feed, drinks water more freely, dung consistency improves, and cud chewing returns. Milk recovery comes later.

Farmers often expect instant results, but metabolic recovery follows biology, not urgency. The role of consultancy here is to set the right expectations and prevent panic-driven wrong decisions.

Why These Case Studies Matter for Farmers

This case is not unique. Variations of this story happen daily across dairy farms. The difference between recovery and loss lies in early understanding and correct direction.

Ali Veterinary Wisdom’s role is not just to prescribe medicines, but to help farmers and field veterinarians understand why the cow reached this stage and how to prevent recurrence in future lactations. That includes transition nutrition planning, rumen support strategies, mineral programs, and early warning signs that should never be ignored.

Final Thought

When farmers search cow not eating, cow not giving milk, or cow not standing up, they are often already late. But with the right guidance, even late-stage cases can be stabilised, and future losses can be prevented.

This is where structured, experience-based online consultancy bridges the gap between field confusion and scientific clarity. That is exactly what Ali Veterinary Wisdom aims to provide – not quick fixes, but correct understanding and sustainable solutions.

Consultancy Call at 9871584101