Delayed Fermentation Intolerance in Dairy Cows

A Metabolic Problem Modern Genetics Created, but Textbooks Never Prepared Us For

When Everything Looks Fine — Until It Isn’t

In many high-producing dairy herds today, a confusing pattern is becoming increasingly common. Cows eat normally, rumination looks acceptable, dung remains stable, and milk production appears steady — for two or three days. Then suddenly, without warning, diarrhea appears, feed intake drops, milk production declines.

Intrestingly, there is no fever, no obvious infection, no dramatic disease outbreak. This situation does not fit neatly into classical acidosis, alkalosis, or infectious diarrhea. Yet it repeats itself again and again in high-genetic-potential animals.

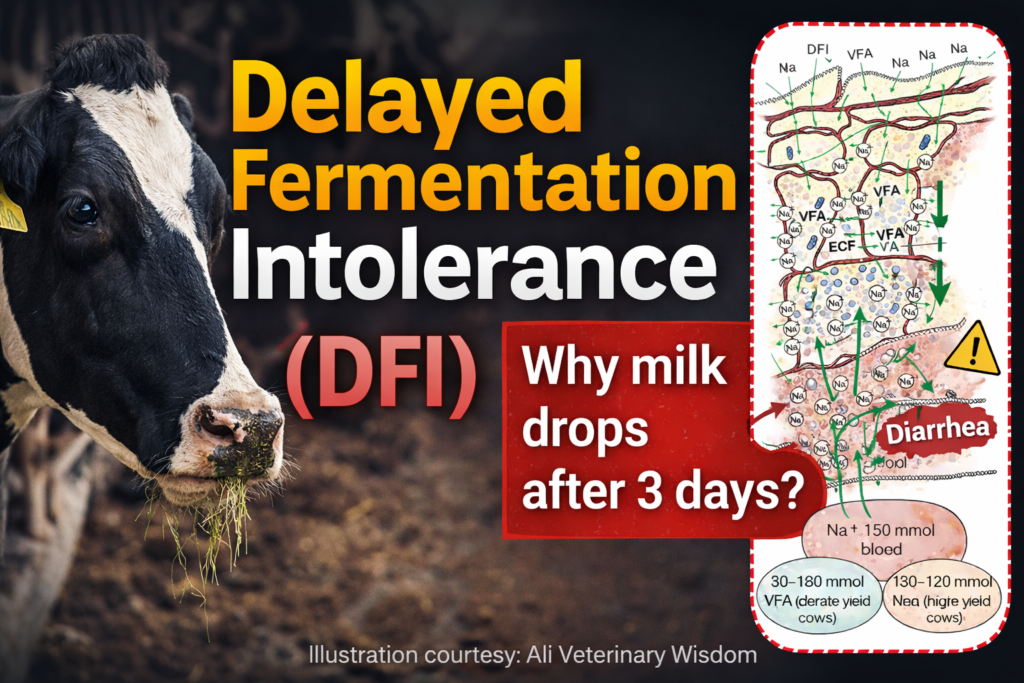

This pattern is best described as Delayed Fermentation Intolerance (DFI) — a functional metabolic failure where the rumen continues to ferment, but the animal gradually loses the ability to tolerate the fermentation load.

What Is Delayed Fermentation Intolerance?

Delayed Fermentation Intolerance is not a disease in the conventional sense.

It is a tolerance failure, not a digestive failure.

The rumen is able to ferment carbohydrates and proteins. Microbial activity continues. But the biological systems that absorb, regulate, and buffer fermentation by-products begin to lag behind.

The defining feature of DFI is delay.

If fermentation were truly toxic, the cow would show signs immediately. Instead, symptoms appear only after cumulative pressure builds over several days.

Is problem me rumen kaam karta rehta hai, lekin us kaam ka pressure cow jhel nahi paati. isliye problem turant nahi, 2–3 din baad dikhti hai.

The Forgotten Organ: Rumen Epithelium

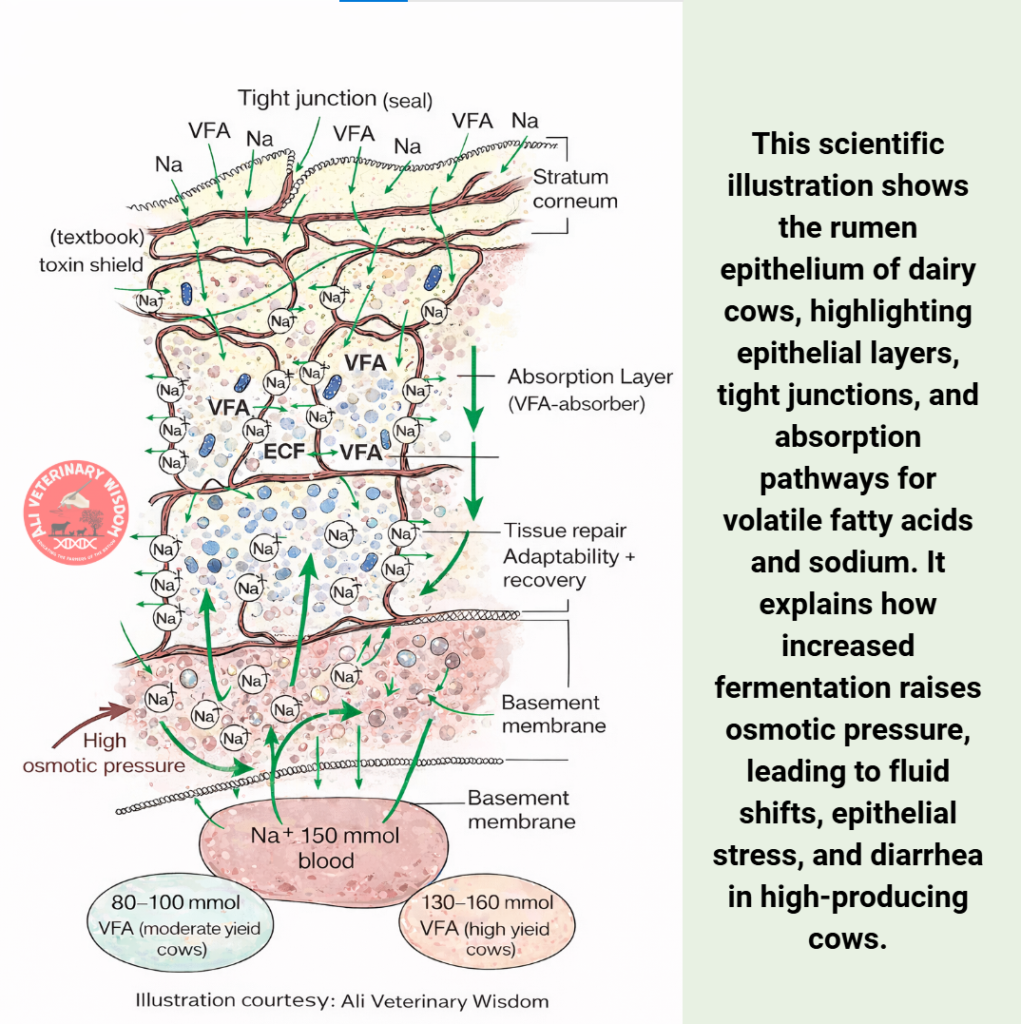

Most nutrition discussions focus on feed ingredients — starch, protein, fat, minerals. Very few people focus on the rumen epithelium, the living tissue that makes fermentation biologically safe.

Microscopically, the rumen epithelium consists of:

- Stratified squamous epithelial layers

- Tight junctions forming a selective barrier

- Papillae that expand surface area for absorption

This epithelium is metabolically active. It:

- Absorbs volatile fatty acids (VFAs)

- Regulates ion transport (Na+)

- Prevents uncontrolled entry of bacteria and endotoxins (toxin sheild)

When this barrier is intact, high-energy diets are tolerated well.

When the rumen epithelial barrier is intact, it performs three critical functions that allow cows to tolerate high-energy diets without developing diarrhea.

First, an intact epithelium efficiently absorbs volatile fatty acids (VFAs) produced during fermentation. VFAs are osmotically active molecules. Rapid absorption prevents their accumulation in rumen fluid and keeps rumen osmolarity within a safe physiological range.

Second, a healthy epithelial barrier maintains tight junction integrity between cells. These tight junctions regulate the movement of sodium, water, and small solutes. When intact, they prevent excessive sodium and fluid leakage into the rumen and intestine, stabilizing fluid balance.

Third, the barrier limits translocation of bacteria and endotoxins into circulation. This prevents inflammatory responses that can further disrupt gut motility and secretion.

When this barrier is compromised—due to osmotic stress, prior acidosis, or metabolic overload—VFAs and ions accumulate, rumen osmolarity rises, and water shifts from blood into the rumen and intestine. This fluid shift is the primary trigger for diarrhea, making diarrhea a functional sign of barrier failure rather than infection.

In short, when it is compromised — due to previous acidosis, osmotic stress, aggressive energy push, transition overload, or liver stress — fermentation continues, but absorption and regulation do not keep pace.

Why DFI Is Not Acidosis (And Not Alkalosis Either)

One of the biggest mistakes in the field is labelling every diarrhea or milk drop as “acidosis.”

But DFI behaves very differently.

| Feature | Acidosis | Delayed Fermentation Intolerance |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Rapid | Delayed (2–4 days) |

| Fever | Sometimes | Rare |

| Response to buffers | Improves | Often worsens |

| Herd pattern | Many animals | Few sensitive animals |

| Root cause | pH crash | Tolerance overload |

In DFI, rumen pH may even look normal when checked casually.

The real issue is fermentation speed, osmolarity, and epithelial stress, not just acidity.

VFA Load: When Numbers Start to Matter

In moderate-producing cows, total rumen VFA concentration typically ranges between 80–100 mmol/L. In modern high-yield cows on dense rations, VFA concentrations can reach 130–160 mmol/L, especially with high starch and sugar intake. Acetate, propionate, and particularly butyrate accumulate rapidly. VFAs are weak acids, but their real impact in DFI is osmotic, not acidic.

When absorption lags, these molecules accumulate in rumen fluid, increasing osmotic pressure.

Osmotic Pressure: The Real Diarrhea Trigger

Under normal conditions, rumen osmolarity remains around 260–300 mOsm/kg.

During intense fermentation, osmolarity may exceed 350–400 mOsm/kg.

At this level:

- Water shifts from blood into rumen and intestine

- Plasma volume is temporarily protected

- Intestinal secretion increases

- Diarrhea appears

Diarrhea infection se nahi hota, balki body ka defence response hota hai. jab rumen ka osmotic pressure limit cross karta hai.

This process can occur even when rumen pH appears normal.

Rumen–Blood Osmolarity Dynamics

The body constantly tries to equalize osmolarity between:

- Rumen fluid

- Blood plasma

- Intestinal contents

In DFI, rumen osmolarity rises faster than blood can compensate. The result is a protective redistribution of fluids — outwardly expressed as diarrhea, reduced intake, and milk drop.

This is physiology protecting circulation, not pathology destroying the cow.

Why Symptoms Appear After 2–3 Days

This delayed onset is the hallmark of DFI.

Day 1: Fermentation increases, epithelium compensates

Day 2: Osmotic load accumulates

Day 3–4: Absorptive and regulatory limits are crossed

Only then do clinical signs appear.

This delay is the most important diagnostic clue.

Secondary Bacteria: Cause or Consequence?

In many DFI cases, fecal or milk cultures show organisms such as E. coli.

This often leads to unnecessary antibiotic use.

In reality:

- Barrier dysfunction occurs first

- Immune surveillance weakens

- Opportunistic bacteria appear secondarily

These bacteria are markers of epithelial compromise, not primary pathogens.

This explains why antibiotics may give temporary improvement but rarely prevent recurrence.

Why Buffers Often Fail in These Cases

When farmers see diarrhea or milk drop, the instinctive reaction is to add:

- Sodium bicarbonate

- Soda-based buffers

- More alkalinity

But buffers only correct pH, not fermentation dynamics.

In DFI:

- Fermentation is already uneven

- Over-buffering may increase alkalinity

- Microbial imbalance worsens

- Osmotic stress increases

This is why some cows worsen after “more mitha soda.”

Why Only Some Cows Show DFI

A consistent pattern emerges:

- Most of the herd remains stable

- A few cows relapse repeatedly

These cows are usually:

- Highest yielders

- Recently peaked animals

- Metabolically stressed individuals

They are not weak cows — they are biological indicators, revealing the true tolerance limits of the system.

Why You Won’t Find DFI in Textbooks

This is where modern dairy farming diverges from classical education.

Most veterinary and nutrition textbooks were written when cows produced 15–25 litres of milk per day. Physiology, nutrition, and disease models were built around that reality. However any cow or even buffalo can face this problem due to reason stated above but incidences are low and often ignored as digestive disturbance but in high yielding cows it is becoming common day by day.

Today’s cows routinely reach 50–60+ litres.

When genetic capacity increases at this scale, physiology must adapt — but these adaptations are gradual, subtle, and rarely documented immediately.

Textbooks us cow par likhi gayi hain jo kam doodh deti thi. Aaj ki cow genetically aage nikal chuki hai, isliye uska biological behaviour bhi alag hoga.

Delayed Fermentation Intolerance is not absent from textbooks because it is unimportant. It is absent because it did not exist in the same form when those books were written. It is a field-derived concept, born from observing modern cows under modern production pressure.

The High Genetics–Low Tolerance Paradox

Genetic advancement has increased production faster than tolerance margins.

Modern cows:

- Partition nutrients aggressively toward milk

- Operate with narrow metabolic safety margins

- Fail through functional overload rather than classic disease

DFI is the biological expression of this gap.

Why Farm-Specific Feeding Matters

No two farms are identical. Silage fermentation, water minerals, feeding frequency, heat stress, genetics — all differ. A ration that works perfectly on one farm may cause intolerance on another.

Water TDS, rumen osmolarity, and Delayed Fermentation Intolerance (DFI) are tightly connected, but this link is rarely discussed clearly. I have discussed it step-by-step, biologically, without jargon overload.

Isliye “copy-paste ration” high yielding cows me fail hota hai. Farm-specific feeding ab choice nahi, zarurat hai.

Non-Specific Advisory for DFI-Prone Animals

Without prescribing formulas, some principles apply universally:

- Energy must be increased gradually

- Fermentation speed matters more than total energy

- Recovery phases deserve respect

- Weakest animals define system limits

These cows benefit from tolerance-friendly nutrition, not aggressive push.

Exact strategies must be tailored — which is why experience-based consultancy matters.

Final Thought

If cows develop diarrhea after 2–3 normal days,

If milk drops without fever,

If buffers and antibiotics fail to provide lasting relief —

The issue may not be disease.

It may be Delayed Fermentation Intolerance — a reminder that in modern dairy cows, tolerance is as important as nutrition.

About Ali Veterinary Wisdom

Ali Veterinary Wisdom works closely with dairy farmers to decode complex metabolic problems in high-producing herds. The focus remains on understanding why problems occur — not just how to temporarily suppress symptoms.